Philip wrote:Hugh, the early disciples/apostles didn't just believe the resurrection was something: They specifically believed: Jesus was/IS God, who took on the cloak of humanity. They believed he died a horrible death on a cross. They believed He was able to come back from the dead, fully alive and healthy, and that He appeared to themselves and many witnesses after rising from the dead. Hugh, is there any of the above paragraph, that the Apostles believed, but you do not?

Philip, I'm afraid I can't make my beliefs as clear-cut as that. I think that, had I been there with disciples, I would have accepted everything that they accepted, and so, since I wasn't there, I'm prepared to believe their story. I

believe, but I do not

know. I really can't do better than that.

How does this apply to the Shroud, you ask? It has everything to do with it!

No, don't think it does. Barrie Schwortz - see below - does not believe in the resurrection at all, nor the salvation that stems from it, nor that Jesus was God, but I find that he is at least as 'Christian' in his behaviour as I am, quite possibly better, in fact, and am certain that he is no less likely to spend eternity in heaven than I am.

Kureiou wrote:In medieval times, nails are represented as going through the palms (not wrists) and feet separately (not on top of each other). If it was medieval artistry, then the evidence suggests the image on the shroud is out of line with what people believed.

One of the interesting things about the Shroud is that not does not show the palms of the hands, so that it is quite incorrect to say that it shows the nails going through them. What people usually mean is that the site of the exit wound on the back of the hands suggests that the entry wound was through the palms. This may seem like quibbling, but the point is important. Forensic pathologist Fred Zugibe, for instance, thought the nail might have gone in at an angle, in through the palm and out through the wrist. Try this: 1) draw, with a sharpie, four dots on your knuckles, four more on the first joints of your fingers, and one big one on the back of your hand, which you think marks where a nail through the palm would exit. 2) repeat this exercise with a picture of the Shroud's hands (but use the exit wound marked by the blood). 3) Measure the lengths of your own first phalanges, and the lengths of the shroud's first phalanges, and the distances from the knuckles to the nailhole on both images. 4) Compare the

relative distances between the nailhole and the knuckles on both images (not the absolute distance, as your hand could be wholly bigger or smaller than the Shroud's. 5) Ponder on the difference between the two...

bippy123 wrote:So hugh, you would have us believe that someone like Barrie Schwartz is totally mistaken on these very important points on the shroud? You do know he's an Orthodox Jew and was sceptical of the shroud and is now a proponent of its authenticity . Tell me why I should believe your opinion and totally disregard Barrie's ?

I know Barrie's views very well, and he knows mine, but we get on very well when we meet, as we both understand that our conclusions are our personal interpretations, but our evidence is the same. He too is a stickler for primary sources. I don't think you should "totally disregard" anybody's opinion, not even mine. You should a) read everybody's opinion, b) check that the evidence upon which they base their opinion is true, c) decide how justified those opinions are, based on the accuracy of the evidence cited, and d) form your own opinion.

Kureiou wrote:Byzantine coins (7th century) show 145 points of congruence to the shroud.

When I type "shroud" and "points of congruence" into Google, I get 4510 hits. Even without opening the irls, the first page gives:

1) no number

2) 188

3) 46

4) "more than 140"

5) 180

6) no number

7) no number

no number

9) 170

10) 170

I expect if I clicked on any of the 'no number's I would get something similar. What you never, ever get is a list of them. Or even a definition of a point of congruence. If you and I both scribbled randomly on squares of paper, and they were then overlaid, there would be dozens of 'points of congruence', all, of course, meaningless. On the other hand if we both drew as best we could, by copying a given drawing, the outline of rhinoceros, and overlaid the images, there could be very few points of congruence, even though both our drawings were clearly identifiable as from the same model. Anybody claiming these 'points of congruence' for the Shroud always claims that that in this or that court of law, you only need this or that number of 'points of congruence' in fingerprints or faces or facial recognition software. I have never seen any of this justified - my insistence on primary sources evident here! - and of course, none of it is true. Dozens of points of congruence between fingerprints can be completely obviated by a single clear demonstration of a point of lack of congruence.

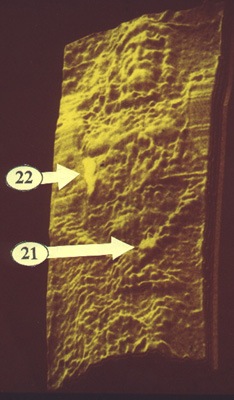

Now let's turn to the coin. Specifically, the crease below the neck you use an illustration. If you refer to the two negatives of the Shroud at:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/ ... o_1898.jpg and

http://www.aperture.org/wp-content/uplo ... _12307.png, and compare the creases visible when Secondo Pia took his photo compared to those visible when Giuseppe took his, you will see that the 'neck crease' did not exist in 1898, and is an artifact of the rolling up of the Shroud between 1898 and 1930. I need hardly add that it's gone again now!

So no, I do not find the points of congruence between the coin and the Shroud compelling. Nor the fact that after his return from exile, Justinian reverted to the earlier style of depicting Christ. Some numismatic historians think this was related to his political allegiances, and the styles of depiction common to each one.